My paper this evening has a family connection. Heather's father, Duncan William McLachlan, Civil Engineer, Class Gold Medalist, McGill 1904, was the winner of The Engineering Institute of Canada's Gzowski Gold Medal in 1924 for his paper "The St. Lawrence River Problem" 1 dealing with ice problems.

McLachlan was a colleague of the late A. L. Killaly, a member of The Peterborough Fortnightly Club in the 1920's. Killaly was the engineer on the Trent Canal and lived in Peterborough on Weller Street. (Mary Rogers, well known in the community, lives in the Killaly house today.)

McLachlan was employed by the Department of Railways and Canals and initially worked on the Trent System in Campbellford.

As a senior engineer, McLachlan protested that Port Nelson on Hudson Bay was the worst possible place to build a port terminal. When McLachlan retired from the Federal Government, he was Chief Engineer Design and Capital Construction, Department of Transport.

McLachlan's speciality was ice including the numerous forms and forces it exerts on structures. Long after he retired at 68 he was consultant to The New Brunswick Electric Power Commission and trekked the St. John River on snow shoes when he was 75 years of age. He also acted as an expert witness on behalf of Calgary Power, now TransAlta, in court cases associated with ice formation on the Bow River in Alberta.

Robert A. Blount, March 7, 1998

The initial interest in opening a route from the prairies through Hudson Bay to Europe developed as Lord Selkirk brought highlanders to settle in the Red River Colony in 1812. The settlers passed through Hudson Bay, the Nelson River to Norway House near the north east entrance to Lake Winnipeg. But very little was said of Hudson Bay until the mid 19th century when a Lieutenant M. H. Synge suggested colonising the prairies by shipping Irish peasants through Hudson Bay. You can imagine such a plan was not acceptable to the Hudson Bay's Company because agricultural development was not supportive of its mission in the fur trade. 2

During the later half of the 19th century a great number of proposals were made to build a railroad to Hudson Bay. It was an era of political pork barreling in every sense of the word.

One group would snooker another while each attempted to secure financing from both the private and government sectors not only in Canada but Britain as well. In fact one very enterprising group proposed building a railroad from San Francisco to York Factory on Hudson Bay some 20 miles as the crow flies from Port Nelson.

In the early 1900's wheat production doubled and grain shipments clogged existing shipping terminals. At the same time the prairies were gaining more political power. In 1905 the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were created and joined Manitoba to provide a strong voice from the prairies. With three provinces now in the prairies, political pressure mounted to build the Hudson Bay Railroad. When the first elections were held in Alberta and Saskatchewan both Liberals and Conservatives demanded that the line be built. At the height of the Alberta campaign, one Liberal announced that the federal government was committed to the task. He was quickly followed by a Liberal candidate in Saskatchewan with the same statement. The statement was not true, yet Sir Wilfred Laurier failed to deny that his government would support the venture. The Liberals won in both provinces. At this point Manitoba entered the fray demanding its border be extended to Hudson Bay to include Churchill and Port Nelson and that the line be built. All this happened at about the same time as the Manitoba sectarian school issue. Laurier, the true politician, took advantage of Quebec's concern with the school issue and began to procrastinate.

In 1906 the grain crop was large. Winter was early and a large portion of the export crop remained in the west. In the following spring, Parliament put rail access to Hudson Bay on top of the agenda. A Senate Committee urged the immediate start on the railroad to Hudson Bay to prevent a repeat of export grain remaining in the west. Yet Laurier hesitated to undertake the project with public funding. He favoured private ownership. With pressure running high, Clifford Sifton came up with a compromise and I quote him as follows:

An election was called in the fall of 1908 and the Liberal party under Laurier promised an immediate construction of the railroad. Survey parties were on their way before the polls opened. Laurier won the election but lost a number of seats in the West.

The Chief Government Engineer John Armstrong headed five survey parties to determine various routes to Churchill and Port Nelson. In the following spring Armstrong reported that the terrain seemed to be less difficult than anticipated. There was little rock work and bogs were a few feet of slime over a great deal of primal ice. He recommended the harbour be built at Port Nelson rather than Churchill because the railway would be 67 miles shorter and cost 16% less.

The Department of Railways and Canals determined that the cost of moving the grain via Hudson Bay would be $3,300,000 a year, the annual cost of operating and maintaining the railway would cost $10,000,000 a year, and would be open for three months and only operate for 30 days a year. On receipt of this information the Cabinet got cold feet and asked that more information be obtained by the Department of Marine and Fisheries but in the meantime construction of rail from The Pas was to proceed before selection of the site for a new harbour.

The Governor General along with a group of distinguished Canadians and Britons went to Hudson Bay in the summer of 1910. One of the visitors reported as follows:

Such a report pleased every one from the West. However, it was not reported that a Captain I. B. Miles who had been relieving hydrographic parties in the Arctic declared that Hudson Strait must be regarded as a dangerous passage at any time of the year until it was fully equipped with navigational aids including more accurate charts, patrol vessels, beacons, wireless stations and an ocean going tug. He also stated that Port Nelson was unsuitable as an anchorage and believed that seaman, who for two hundred years, had preferred Churchill for good reasons. At this point Laurier didn't want to push the railway and chose reciprocity with the United States as the Liberal platform in the 1911 election. On the other hand the Conservative platform called for the immediate construction of the Hudson Bay project.

After the election of the Conservative government, the new Minister of Railways and Canals sought background information on the project and was so concerned with unwarranted assumptions and guesswork calculations that he halted work until a reappraisal could be made. Western members of Parliament were furious and forced Robert Borden to order continuation of the project. Port Nelson was chosen as the terminal for the railway after a visit to both sites by the Minister and Chief Engineer H. A. Bowden.

D. W. McLachlan, Chief Designing Engineer of the Department of Railways and Canals was sent to Halifax early in June 1913 to supervise the loading of ships with materials and supplies for the port facility at Port Nelson. Against his protest he was assigned to be in charge of the work at Port Nelson and soon found himself on board one of the vessels heading up to Port Nelson. He threatened to redirect the fleet to Churchill and was told he would be put in irons if he did so. It was a difficult voyage: two ships were stuck in the ice of Hudson Strait for 10 days; the Alette punctured her plates, was beached and burned; the Caerense grounded and was abandoned; one ship was obliged to return to Halifax without discharging her cargo.

On arrival at Port Nelson workmen's tents and cookeries had to be completed, derricks erected, swamps drained, railway tracks laid, foundations excavated, warehouses built, rolling stock landed, supplies protected from fire, rain, frost and theft, all of which operations were interdependent and each obstructed by non-completion of the other.

The buildings were erected as quickly as possible in order to house the workmen and protect supplies. By the end of October three bunk houses, one dinning camp, a retail store and office, two warehouses, a meat house and a root house were in place The hospital was completed just prior to Christmas. At that time there was two miles of narrow gauge track in use. The rail track was used rather than roads to move equipment and workman through the camp right up to the bunk houses and other buildings. A monthly transportation service by dog team between Le Pas and Port Nelson was operated throughout the winter in order that pay-roll and mail should not be long delayed.

When all supplies were in warehouses, work began on building the wireless station to communicate with Ottawa. Foundations were dug in frozen clay and concrete laid in November and December at temperatures twenty degrees below zero on many days. In this environment two 250 foot towers were erected in the windy cold winter condition. It was not until late February that the station was fully operational.

During the latter part of February a gang of fifty men were moved to the opposite side of the Nelson River to cut native lumber for temporary structures. Since there were no horses and the dogs were used to haul provisions, the men themselves hauled the logs on small bobsleds. Over 10,000 pieces were moved this way before the end of the season.

Early in the winter it was realised that coal was short and in order to have sufficient for the coming spring's work it was decided to burn wood. A lot of time and money was spent hauling wood for fuel from the sparsely wooded creeks and ridges near the camps.

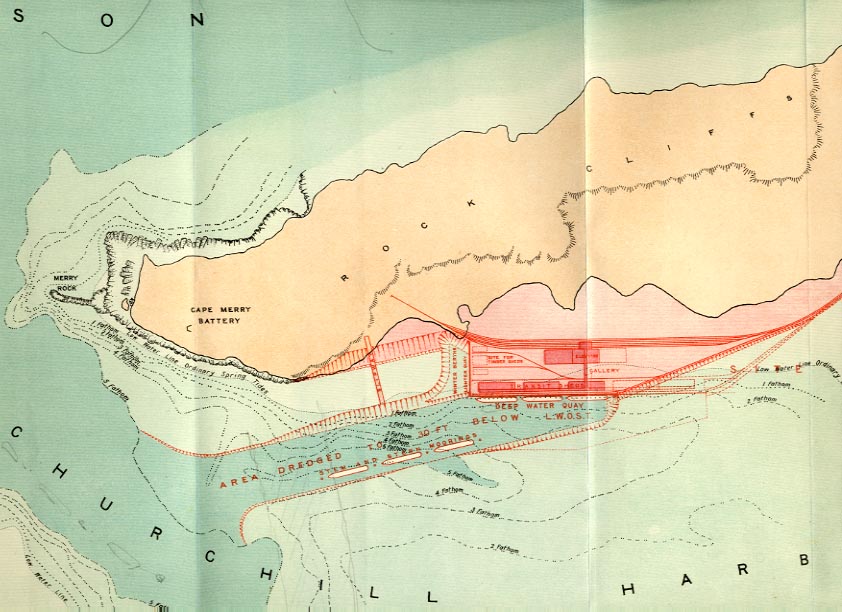

Please refer to the plan of the Nelson River Estuary. In the north east quandrant of the drawing there is a reference to Natural Channel and beneath the words are the numbers 17, 18 up to 22. These are the miles from the location of the proposed port terminal. Now imagine an east wind blowing into the constricted mouth of the Nelson River.

McLachlan felt he was working on a hopeless cause. He was appalled at the ice conditions and wrote:

At the five mile distance from the terminal you will see a reference to the wreck of the ship "Alette". Above the 1 mile point there is a note "Original Scheme" and this is where McLachlan had inherited a plan to build a long jetty. He didn't like the plan because he felt any diversion would silt the existing channels.

Please refer to the drawing "Possible Port Terminal At Port Nelson". In the upper right corner you will see a reference to Root Creek and abandoned initial scheme. McLachlan built the scheme as a short experimental pier which justified his fears by silting approaches to the point that a suction dredge was powerless to reopen the channel.

Please refer to the aerial photograph of the pier entitled "View of an attempt to run out a solid jetty from the shore at Nelson, causing rapid silting on either side and excessive scour at the end." You can see Hudson Bay at the horizon and the build up of the silt in the foreground. This site was abandoned.

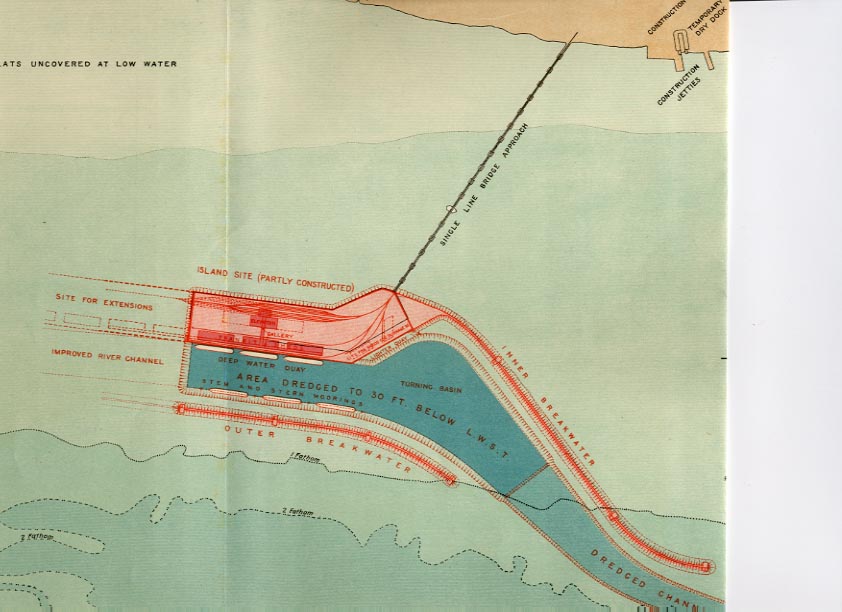

McLachlan came up with an alternative and you can see its partial completion on the drawing. In order to take the shock of the ice and to divert the silt he decided to build an artificial island 5,000 feet long and 4,000 feet wide on a rocky ledge 1,300 yards from the northern bank of the estuary. There would be breakwaters on three sides of the island providing shelter for quays and anchorages. A bridge of 17 spans would be erected between the shore and the island.

In the centre of the drawing you can see the single line bridge approach to the island that is partly constructed.

In December 1914 McLachlan went to Montreal to consult with Sir John Kennedy, the creator of the port of Montreal. Kennedy approved of McLachlan's plan but Chief Engineer Bowden continued to voice his objections. The file containing this continuing struggle between two engineers was becoming very large and could turn into a politically explosive document. Finally in the summer of 1915 McLachlan was summarily dismissed. He remained on duty pending the arrival of his successor. No one ever turned up so he worked on. (It is interesting that in 1927 the Minister of Railways and Canals reminded him he had been drawing salary for 12 years without warranty).

By the fall of 1917 the bridge and about half the island had been completed but the project was grinding to a halt. All work stopped by mid December because of the need to direct all the country's resources to the War effort.

During the summer of 1917 McLachlan began to suspect the accuracy of his charts. When the work had closed down he received permission to build triangulation beacons and to undertake new soundings. He discovered shoals on what was supposed to be an unobstructed passage and, more surprisingly, a wide, deep channel that was not shown on the charts. This discovery transformed the situation and made the project feasible. He admitted his error in stating that Port Nelson was impossible and concluded he could do something with the port.

In 1918 F. H. Kitto of the Dominion Natural Resources Branch, on returning from summer work at Hudson Bay reported a storm, that had rendered the Port Nelson anchorage unsafe. The same storm scarcely ruffled the surface of Churchill harbour. These views were presented to cabinet and a Special Committee of the Senate under took to examine 'the character of the ports of the said Hudson Bay with regard to their fitness as railway terminals'. McLachlan was called to appear before the committee. He requested permission to read a prepared statement before questioning began. McLachlan described the nature of the land, the weather and living conditions, the problems of construction in the north and the physical nature of the port facility. Members of the Senate Committee knew nothing about the north and were so fascinated that it took two days for McLachlan to finish his prepared statement. Other witnesses appearing before the committee included Vilhjalmur Stefanson, the Arctic explorer, numerous missionaries, police officers and sea captains.

In December 1921 the Conservative government was defeated and Mackenzie King was elected Prime Minister. He needed support in the House from some 66 western MPs who were pressing for the resumption of construction of the railroad and the Port Nelson terminal. So it was arranged that in the spring of 1922 McLachlan would prepare a new estimate to complete the project. McLachlan's estimate was $21 million and he recommended against the project and that the railway be reduced to a local line. This resulted in an Order-in-Council authorising the raising of 120 miles of track to be used elsewhere. When the West found out what was happening they forced the government to rescind the Order-in-Council. This entire incidence re-ignited Western Canada's demand for rail access to Hudson Bay.

In the 1925 election, King badly needed the support of the Progressive party to form a government. You may remember The Progressive Party was made up of Members of Parliament from the Prairie Provinces. The Speech from the Throne revealed that the price to be paid for the Progressives support was the construction of the Hudson Bay Railway without delay and the rehabilitation of 332 miles of line. There was an eruption in the House and the Senate over the cost.

In September 1925 Charles Dunning, the former premier of Saskatchewan, took over as Minister of Railways and Canals and ordered a new survey of the route from Kettle Rapids to Churchill. Dunning hired Frederick Palmer, an English port engineer, to advise in the port facilities. Dunning and Palmer travelled to Port Nelson together. As Palmer viewed the work at Port Nelson he commented:

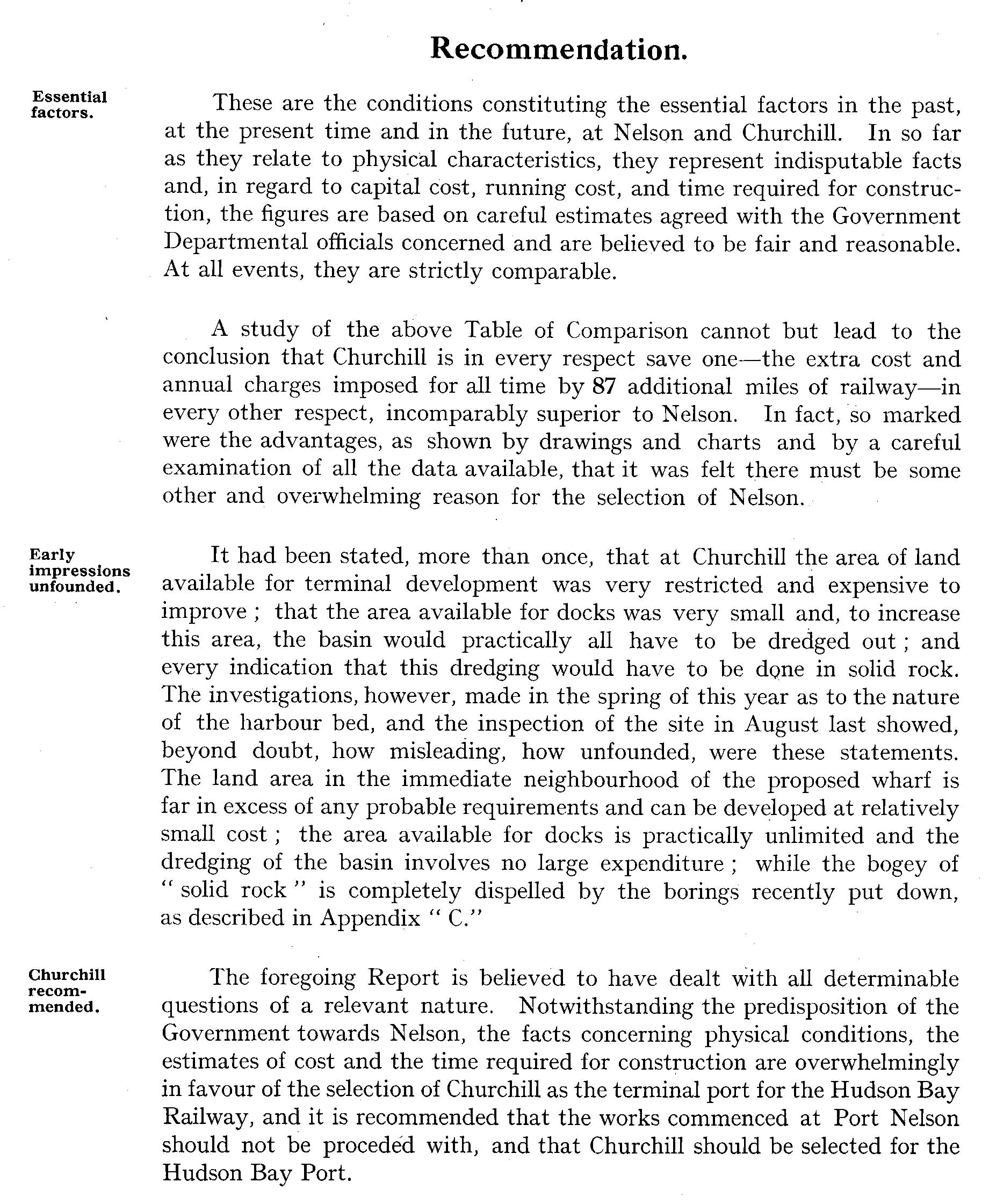

Dunning declared that Port Nelson must be written off and a new start made at Churchill. Churchill had a harbour; Port Nelson had none. The Palmer Report was submitted to the Government in the fall of 1927. 3

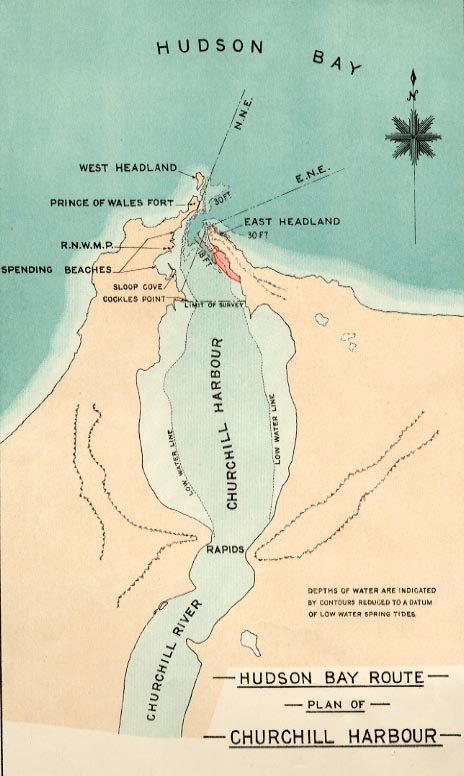

The drawings "Hudson Bay Route - Plan of Churchill Harbour" and "Hudson Bay Route - Possible Port Terminal at Churchill" are Sir Frederick Palmer's suggested layouts for the harbour and port terminal.

The Churchill River emptied into the harbour 12 miles from the sea. The entrance to the harbour was a deep and narrow passage between two high headlands. There was no silting problem and more harbour space was available than ever would be needed. Churchill became the terminus on Hudson Bay and became operational in the summer of 1931.

The port terminal, updated to July 24, 1996, is shown in the drawing Map of Churchill Wharf. 4

This last September the G & M reported that Lloyd Axworthy 5 extracted about $50 million from the federal and provincial treasuries and twisted arms all across Western Canada to keep trains running in Manitoba and to resuscitate the Port of Churchill. CN agreed to sell to a private rail operator, OmniTRAX for $1 (but only after Ottawa had paid $16 million to compensate it for the loss of scrap if CN had torn up the track.) OmniTRAX is based in Denver, Colorado.

OmniTRAX agreed to run the Port of Churchill if the Federal government put up $110 million for health and safety measures, and additional money for a hopper-car unloader, grain cleaners, sewage treatment and concrete restoration. There will be a new tug and new wharf face. Dredging to accommodate larger ships will cost another $16.5 million of which $6 million comes from Manitoba. The port terminal will be operated by the Hudson Bay Port Co., a division of OmniTRAX. "It is a port that has a bright future as Canada develops two-way trade with Soviet Union and other Eastern European countries" claims Bev Desjarlais (MP-Churchill) NDP Transport Critic, House of Commons, Ottawa. 6

This past week the Globe and Mail reports that Ottawa will spend $2.1 million on a new Churchill air terminal according to Transport Minister David Collenette. The new building will house airline offices, ticket counters, baggage and passenger areas. Construction will start in July and take 19 months. 7

The story of Hudson Bay's railroad and port facilities is, in a way, a tail of political compromise that has continued for over a century. In 1996 slightly more than 300,000 tonnes of export crops were shipped from Churchill and this represented about 1 percent of the 29 million tonnes shipped from Canada. A spokesman from the Hudson Bay Port Co. says it is possible to put 2 million tonnes through the facility 8 (That's about 7% of Canada's 1996 shipments). I'm sure all Canadians hope that the new facility will be profitable not only for OmniTRAX but all Canadians as well.

Churchill Proposal

River ..?

Nelson Proposal

Recommendations

View of an attempt to run out a solid jetty form the shore at Nelson, causing rapid silting on either side and excessive scour at the end.

Rough water experienced at the island site at Nelson during a North East breeze, 6th October, 1917.

Big sea, Crib-end Wharf 3 at Nelson, 14th September, 1917. Wind North West.

Approach Bridge during North East Breeze, 6th October, 1917.